B. Couturaud (ed.), Early Bronze Age in Iraqi Kurdistan, BAH 226, Presses de l’Ifpo: Beirut 2024.

K. Gavagnin, M. Iamoni and R. Palermo, “The Land of Nineveh Archaeological Project: The ceramic repertoire from the Early Pottery Neolithic to the Sasanian period”. BASOR, 375, 2016, 119–169.

K. Kopanias and J. MacGinnis (ed.), The archaeology of the Kurdistan region of Iraq and adjacent regions, ArcheoPress, Oxford, 2016.

M. Lebeau (ed.), Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean (ARCANE), Vol. I: Jezirah, Turnhout: Brepols 2011.

M. Lebeau (ed.), Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean (ARCANE) Interregional/1 Ceramics, Turnhout: Brepols 2014.

D. Morandi Bonacossi and M. Iamoni, “Landscape and settlement in the Eastern Upper Iraqi Tigris and Navkur Plains: The Land of Nineveh Archaeological Project, seasons 2012–2013”. IRAQ, 77 (2015), 9–39.

C. Pappi and C. Coppini, “The Plain of Koi Sanjaq/Koya (Erbil/Iraq) in the 3rd Millennium BCE. History, Chronology, Settlements, and Ceramics”, in B. Couturaud (ed.), Early Bronze Age in Iraqi Kurdistan, BAH 226, Presses de l’Ifpo: Beirut 2024, 71-84.

P. Pfälzner and P. Sconzo (with a contribution by I. Puljiz), "First results of the Eastern Ḫabur Archaeological Survey in the Dohuk region of Iraqi Kurdistan. The season of 2013". Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie, 8 (2015), 99–122.

P. Pfälzner and P. Sconzo, “The Eastern Ḫabur Archaeological Survey in Iraqi Kurdistan. A preliminary report on the 2014 season". Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie, 9 (2016), 10–69.

E. Rova (ed.), Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean (ARCANE), Vol. V: Tigridian Region, Turnhout: Brepols 2019.

E. Rova, The origins of North Mesopotamian civilization: Ninevite 5, chronology, economy, society. Brepols, 2003.

J. Ur et al., “The Erbil plain archaeological survey: Preliminary results, 2012–2020”. IRAQ, 83 (2021), 205-243.

K. Xenia, R. Koliński, D. Ławecka, Material Studies. Prehistory. Pottery, Lithics. Settlement History of Iraqi Kurdistan, vol. 11.1, Harrassowitz Verlag: Wiesbaden 2024.

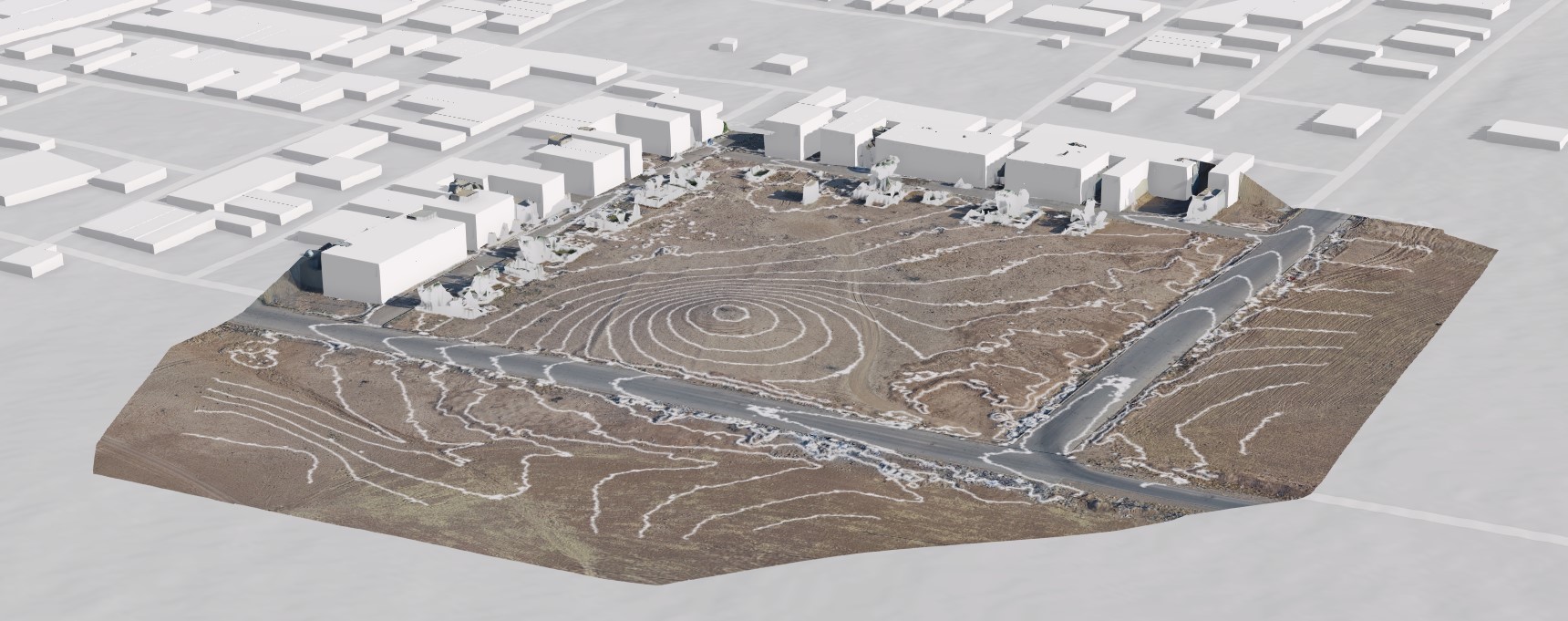

Image curtesy of J. Ur (EPAS)

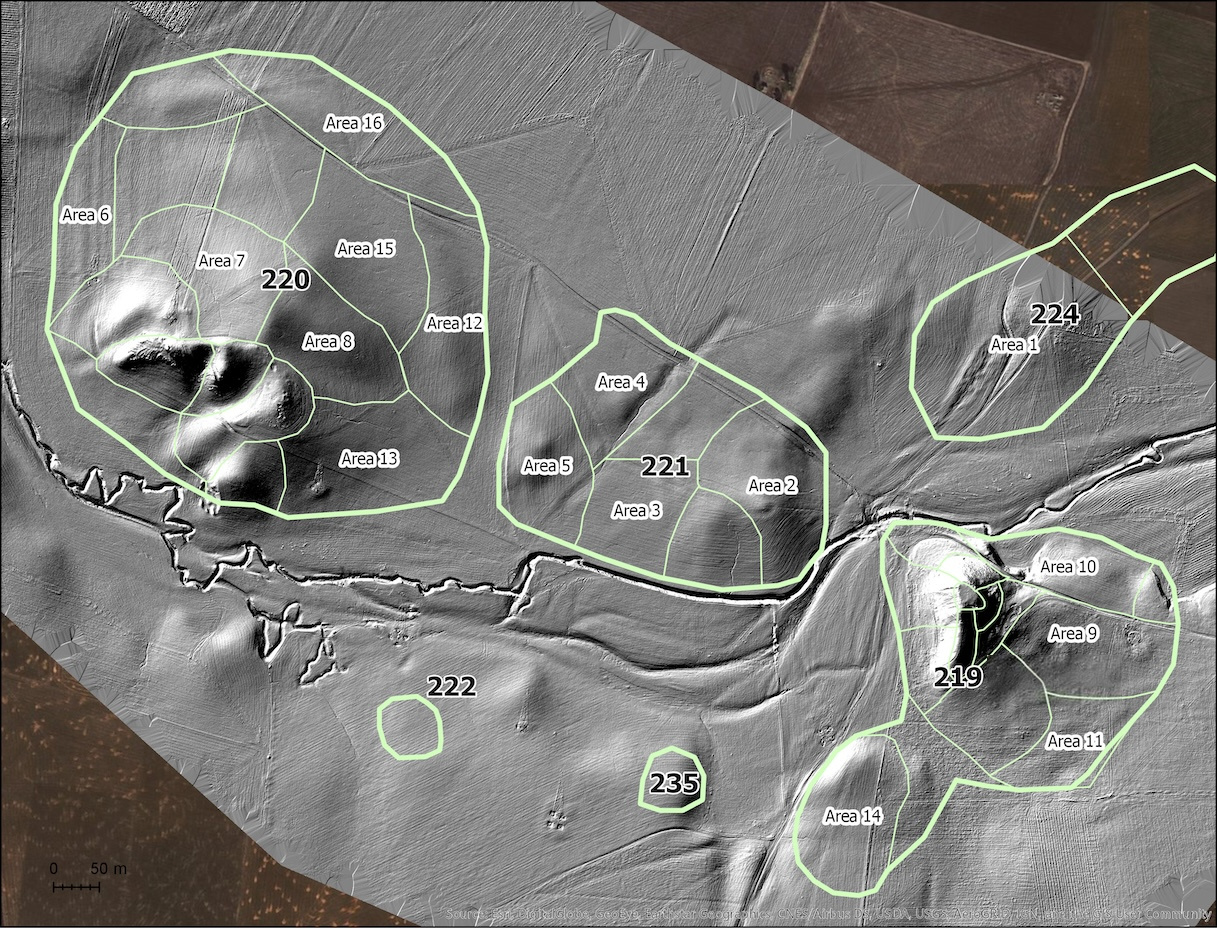

Image curtesy of J. Ur (EPAS)